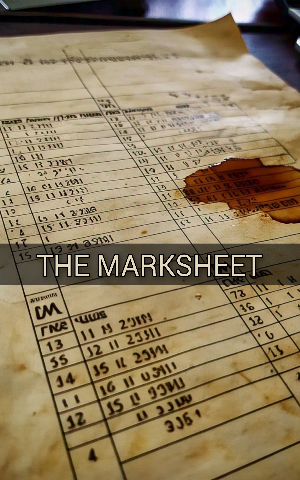

The Marksheet

The Marksheet

They said she used to wear white sarees in the summer and a maroon cardigan in the winter, even when the sun glared down like a cruel god.

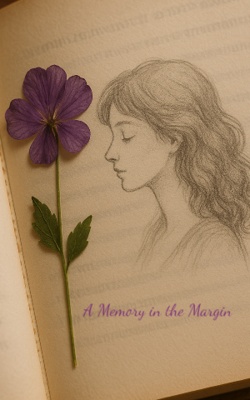

Her name was Champa, like the flower; sweet-sounding, fragrant in memory, but brittle when pressed between the pages of time.

She appeared every Monday, without fail, at the rusted gates of the college, holding a red jute bag that had faded into a dusty rose.

Inside it were papers. Certificates. Applications. Xeroxed marksheets. Letters to the Vice-Chancellor. Notes to the Chief Minister. Petitions to the President. All worn thin by her own fingers.

“I was a gold medallist,” she’d say to anyone who’d pause for a second too long.

“They’ve buried my marksheet. They’ve hidden my degree. Ask the Principal. Ask the Controller. They know. But they won’t say it.”

Students laughed at her, professors avoided her, and clerks said, “She’s been coming for twenty years.”

The receptionist had changed twice, but Champa remained, an immovable glitch in the system.

“She speaks such fine English,” some whispered.

“She used to be brilliant, they say. First-class in Part I and II.”

“Some say she even got admission to a PG course in Calcutta... but the graduation wasn’t complete.”

No one knew for sure. The files were long gone, the registers eaten by time or termites. But she remembered. Every paper. Every teacher. Every classmate who went ahead without her.

Her mother, she said, had been given shocks. “Electricity. To burn the brain. But my mother was not mad. She just believed me.”

She carried her mother’s hospital prescription in her bag, too. It was now unreadable.

One day, a curious clerk asked gently, “Didi, what will you do when you get the marksheet?”

She paused for the first time in years. Then said,

“Frame it. Put it on the wall. And finally, sleep.”

That winter, she didn’t come.

Not on Monday, nor on Tuesday, not even on Saraswati Puja, when she’d usually bring yellow flowers and leave them near the college steps.

Some say she died.

Some say she went mad completely and was institutionalized.

One woman swears she saw Champa at a temple in Assam, barefoot, handing out halwa in silence.

But her red bag remained.

One day it was found beneath the neem tree inside the campus. Tucked inside were clippings, petitions, and—oddly—a hand-drawn certificate with her name on it.

“Champa Dey, B.A. (Hons.), 1st Class, Gold Medallist. With dignity and grace.”

Signed with a fictional registrar's name, in her own curled handwriting.

No one dared throw it away.

It now lies in the dusty archives room, between forgotten syllabi and broken ceiling fans—just as she wanted, perhaps:

Preserved. Believed. Framed.