The Great Indian Resignation

The Great Indian Resignation

“The Great Indian Resignation” headlines screamed at me when I opened my smartphone to catch up with the daily news. The report went on to claim as per a survey of employees that nearly 86% of them were planning to resign in the next six months. Work-life balance, flexibility, not wanting to commute, and working from home were listed as reasons and pay took a lower place. My mind wandered to another report I had read a few months ago. It was shocking when I read it the first time. It claimed that only one per cent of Indians earned more than 100 K Rupees per month from organised employment and the number increased to ten per cent if one brought down the sum to Rupees twenty- five k. Now add to this a recent report from a prestigious magazine that claimed that only seventy per cent of Indians managed to have one decent meal a day. I wondered where was India going? The aspiring viswaguru!

It was then Neelkandan called. Neelkandan drives a Meru Taxi. He was introduced some years ago by my sister. Since then, he has become friendly. He was always well dressed in white as he took his job seriously. He was polite and punctual. Once I had engaged him to drop my friend to the airport. My friend had called from the airport saying that Neelkandan was such a good driver and very civil. I engaged him a few times when I needed to go to the airport for some office work. Work or not he failed to call me a few times a year and we engaged in mutual enquiry about our well-being. COVID forced him to move to his parent's village in Krishnagiri, a district in Tamilnadu famous for mangoes, just about 100 km from Bangalore. With no business, he said at least they had a roof and something to eat. They were able to assist his dad in the farm labour required. My daughter often complains that she was unable to get Uber or Ola. A report explained that many drivers had returned to their natives and their vehicles were being confiscated due to non-payment of dues. This had resulted in a shortage of Ola or Uber taxis in Bangalore.

Neelakandan’s voice was choked when he had called. He had just recently shifted and gotten back into the business. He was stopped by the henchman of NBFC who stopped his vehicle and took away the keys when he was going outstation with a customer's family. He just about managed to get another taxi for the customer. He then called me as he wanted to share his sorrow with someone. He had then called. I didn’t have anything to console him but listened to him sharing his sorrow. Even I too felt choked.

I then went for a walk to change my mood and thought of a cigarette when I felt very stressed. It was then I bumped into Rafiq. he was one of the boys I had met on a train from Howrah to Bangalore. It was one of those early days when I was into my writing and decided to take a sleeper class train. I knew I would meet people and gather some stories.

Rafiq was sleeping on my berth when I woke him up at midnight as the train left Howrah station. The coach was packed like it was a refugee train. In the coupe instead of eight allotted passengers, there were some fourteen people I had counted the next day morning. Rafiq was kind enough to vacate my berth and I caught up with some winks until I was woken up by shouts of vendors selling tea. Rafiq came to sit by my side and inquired if I could sleep well. I had by then decided that I would rather be pleasant and hear his story rather than feel angry at the encroachment by unreserved passengers.

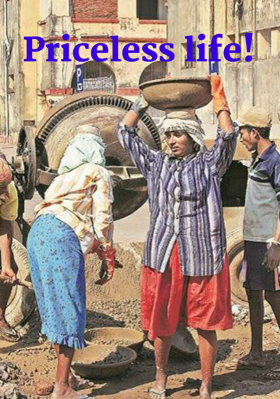

Rafiq was one of those trying out their luck in the so-called paradise called Bangalore. His friend was already there from the same village and had been calling him to join for some time. The deal was thus: he would be offered accommodation which he had to share with his friend and a few others and would be paid Rs 500 per day and work involved six days a week with Sunday being a holiday. The accommodation was basic enough that they got a place to sleep and managed to cook one meal to cut costs. Still, they could earn some thirteen to fifteen thousand rupees a month and remitted about eight a month, A big deal in their parts considering monthly wages in their state capital was just about Rupees five thousand only. They did get a festival bonus of one month's salary.

When I met him that was Rafiq’s first time in Bangalore. A few months later when I met him at my apartment, he was engaged in some masonry work by the contractor who was engaged to do some garden work. But when the second wave of COVID struck Rafiq lost his job along with his village mates.

Our housemaid too got infected with COVID. Considering that she had some illness prior to COVID her recovery took a long time that we had to engage another maid to substitute for her absence. There were many such cases of people losing their livelihood.

To whom do they give their resignations? Such people like Neelakandan had no employment guarantee, and no social security. Nobody issued them appointment letters and no question of tendering resignation letters.

They had resigned to their fate. What one sees is the tip of the iceberg. Like the iceberg, the real horrid storey remains unseen or unheard.

Yet some leaders see some green shoots. Some other claims India will reach a 20 trillion-dollar economy in a few decades. In the meantime, physical hunger if not claiming lives stunts the growth of children. While a different hunger for past glory drives politicians and their blind followers to stoke up fire and fear about other communities who follow a different God.