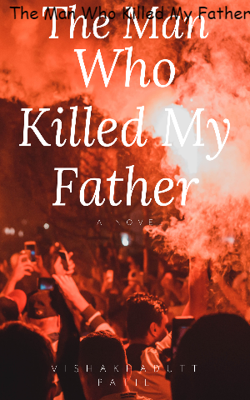

The Man Who Killed My Father

The Man Who Killed My Father

My first memory was seeing him at the bus stop, his spotless white kurta fluttering in the breezy morning air. It was December I think, because I was thinking about the New Year and what surprises it would have in store for me. But now I know that he was always there at the same bus stop waiting for the same bus that would take us to the same college.

1966 was difficult and sweet at the same time. Difficult because starting college meant buying sarees and blouses and petticoats too. School had the simple white salwar kameez with a blue dupatta and one could easily slip into Bindiya’s uniform, which her mother would donate every year to me along with her text books. Life was not that difficult as all I needed was a slate and a note book. I would collect bus tickets, luckily printed only on one side, and staple them together to make mini notebooks. School was simple and uncomplicated. Poetry had no hidden meanings, only figures of speech.

Bindiya’s parents had decided that she would not go to college but prepare to get married. But Ma and Mausi had decided to put me in college. “She should get an education and be able to get a government job. That will ensure that she will always be ... Mahafuuz.” To me “Mahafuuz” meant safe. How would getting a government job give me safety and protection was beyond my understanding. But Mausi had made up her mind and Ma never questioned Mausi. My mother and her sister shared a special unspoken relationship. Unspoken because very few words were exchanged but yet each would know what the other needed. Ma always listened to her sister and for me, my aunt was a window to the world. She would always be telling me what to do, how to talk to people, how to keep people at a distance and what favours were to be politely and tactfully refused and what to thankfully accept.

As I grew up, Mausi would tell me how the things around me had changed too and had acquired new roles. For example the dopatta was no longer a scarf you could use to cover your head, which was long and wide enough to carry all the mangoes you could collect from the lowest branches of the trees; it was now the protector of a woman’s modesty and had to be worn at all times from shoulder to shoulder. And if you discovered that man’s eyes were focused on your dopatta it surely meant that it had slipped from its desired position and was to be immediately adjusted and corrected.

The saree was to me merely a six yard long dopatta that covered your entire body. It had the same function – protecting a woman’s modesty and one was to ensure that it was correctly draped at all times. Modesty, honour, reticence, and politeness were the desired qualities that a woman must inculcate. Indeed Mausi taught me the difference between a woman and a girl. Ma would always meekly listen to Mausi’s sermons and admonitions. So in a sense wasn’t Ma the ideal woman? And wasn’t my brash, outspoken, nagging, and quarrelsome Mausi the very antithesis of her own teachings? This passing thought did linger in my mind but I wouldn’t dare ask Mausi about it.

Moreover one had to be careful about bending down to pick up things. According to Mausi, we must now ensure that our dopatta does not fall in the process of bending down, even when we are bending down to touch the feet of our elders in order to seek their blessings. Mausi told us that one should desist bending down but rather kneel down as this was a ‘safer’ alternative.

It slowly dawned upon me that the world seemed to revolve around a man’s eyes. Mausi would tell me to beware of those searching eyes. Those malicious windows that reveal a man’s dirty desires – were to be studied at all times. They would tell you about the man’s character. Whether he was to be trusted or to be politely relegated to a safe distance – would depend on what his eyes would tell you.

“A man that looks into your eyes and talks to you is safer than a man who looks elsewhere. “ Mausi would tell me.

But I would protest. “How can that be an indicator of safety?” I would stubbornly ask.

“Well he isn’t looking elsewhere. He isn’t attracted to anything else. So he’s okay.”

“But Mausi, what if he’s fooling you? What if he’s really looking where he wants to look when I am not aware?”

“Nothing, nothing really can help a woman in today’s world my child. Mumbai is a bad city but still not as bad as the others. Maybe Delhi is even worse. Maybe Calcutta is safer. But never mind my child. Once you have a government job, everything will be alright.”

This circuitous logic always baffled me but I could not ask Mausi the barrage of questions that kept flooding my mind. For a start, who teaches a man’s eyes to behave? Is there some Mausi that instructs men that to look at what you are attracted to is bad and immoral? And what are they attracted to? Why? And how would you get attracted without first looking?

I had never really had a lot of boys in my play group and my closest friend, Bindiya had no brother. Bindiya’s father worked in a garment factory and would get a calendar every year for his house that had pictures of men and women wearing the fashions of the day. Every January we would wait earnestly for the calendar to see all the pictures for all the months of the year. We would admire the colours and prints on the lovely clothes that we could never even aspire to wear. Whenever a picture of a woman in a transparent saree emerged, Bindiya’s mother would mutter,

“Oh God, look at these shameless women! They will spoil our girls.”

“If we have instilled virtue in them, why should we be afraid? No amount of films or pictures will spoil them.” Bindiya’s father would retort with a smile.

I never dared to imagine that Bindiya’s father would have the eyes that a girl like me should be afraid of. Nor did Mausi ever suggest that I should stop talking to Bindiya’s father now that I had grown up. But she would definitely ask us to stay away from a few men in our neighbourhood, now that we had grown up.

Sunder chacha was one such person. He would always put on the garb of the good neighbour and come inquiring about our well being on his way to work every day. But Ramaa mausi would always follow him on some pretext or the other. She would sometimes give him a shopping list of things that she wanted him to bring on his way back home or sometimes tell him about a chore that he missed. Perhaps she knew about her husband’s intentions and wanted to prevent him from getting too far. I did begin to notice that his eyes would be all over the place. He would notice every movement in the house. I noticed how he noticed that I had grown up. I suddenly felt so afraid of his shamelessly probing eyes. That was when I realized what Mausi meant about men who were safe and men who were not.

Had father been here, how would he have reacted to my growing up? Would he not change at all and remain just the same as Bindiya’s father? Or would he become all the more protective? Come to think of it, I could see that Bindiya’s father had also changed. Earlier, he used to hold Bindiya close to him and plant a huge kiss on her cheek for the good marks she scored in her exams. But of late he would just put his hand on her head and say, “God bless you my child.”

Touching had now acquired a meaning. Mausi used to tell me, “Beware of men trying to touch you or trying to brush past you in a crowd.” Men were everywhere. They were always out to pounce on you. Suddenly you are not a person but an object of desire. What is it that men want to do to women...the stuff that makes babies? My friend Salma started wearing a long gown and a scarf over her head in our last year in school. She told me that was called the Hijab – a dress that will prevent women from being viewed as objects of desire but rather as persons with identities. I thought this was a bit unfair as men must be taught how to behave. “Ah, men will be men...always!” Mausi used to say. “Except when they are fathers or brothers to somebody...” Salma told me. A woman is safe with a male relative who is her guardian. But then the men who roam the streets are fathers and brothers of somebody at home. Why then would they unleash their so called misbehaviour on other women?

I guess all men are not like that. Because our mothers got married to men and we too will be married off to someone from a good family. Life changes when you grow up. The world is no longer trustworthy. It has become a big bad place. I could understand Mausi’s changed behaviour.

“A girl without a father would be an easy target.” Mausi would say. “I am only trying to play the father in the house, to do what your father would have done.”

I guess fathers also change when their daughters grow up. It is a part of their growing up too. They do become more detached though only outwardly but deep inside they are as scared as hell. Bindiya’s father would get very nervous when we took a while longer to return from errands or a visit to the temple. He would bombard us with a barrage of questions and always tell us not to spend too much time looking around at the shop windows but walk back straight home. His voice would be much softer than the admonishments we were submitted too when we were held up for mischief in our earlier days. Clearly his love had not withered, it had only changed.

I missed my father every day. Every morning I would look at his framed photograph and wonder what t would have felt to be n his arms. To be cared for by him. I had never seen him. He passed away when I was still in Ma’s womb, but I would dream of hearing his voce speaking to me from the world outside telling me what a beautiful place it was. And whenever I looked into his eyes staring at me in the photograph, I always found them looking into my eyes. Those were the eyes I should look out for in every man I came across. Eyes that would make me feel comfortable and assured.