PIED PIPER

PIED PIPER

The boy should have known something was wrong the moment he glanced back over his shoulder, but he was too tired and wary and afraid to register the truth. He followed the sound of the keening pipe. Its unfamiliar melody, absurdly cheerful, jarred him from the carnage. It filtered through the pores of his skin and infused him with the strength and warmth he needed to run through the icy clutches of winter.

The forest muffled the sounds within and beyond it as if the trees themselves swallowed noise—all but the tune of the unseen piper. Time stood still, cradled between the labyrinth of jutting roots and a cotton-cloud sky that was falling apart. Tufts of snow floated down through naked branches as if massive pillowcases had exploded during a massive pillow fight between massive gods who did not care that far below them the falling snow sizzled against flames that devoured a village.

Run, his mother had rasped, pushing him through the back door of their home, the door that led to the chickens and pigs, and he’d run until he’d fallen, slipping in the snow and in the refuse of the squealing animals, his vision fractured by his tears. He turned back then, ashamed to have run, ashamed to have left her, even though she no longer quite looked like his mother.

Once she’d been beautiful—the belle of the village, people said. Then the red blotches appeared, lesions that began on her arms and spread across her chest and throat, an army of ants beneath her skin that disfigured her face and body. She did not cry out when she cut a finger or burnt her hands in the kitchen. Her once-lush hair fell from her scalp like shorn wheat, littering the floor in clumps. Yet her eyes were always his mother’s eyes, calm and blue and cool like a damp cloth against a fevered brow, radiating such love that he felt she embraced him even when she avoided touching him. She was all he had left, the only person who cared enough to weep and caress his face when lesions spread across his own back and grew thick like the pedicles of a second spine.

When he crept back into the house, keeping to the shadows, the boy found nothing left of his mother but a dark stain on the floorboards that streaked from the kitchen to the bedroom. A man appeared in that doorway, his body and face sheathed in fabrics and spells that would not let the infection touch him, gripping a sword that wept red tears from its edge. The boy hid until the man turned away, and then sprinted back out into the night. He ran through the streets, dodging the hooves of horses and the torched firewood that the yelling soldiers threw his way.

He fell only once, when something sharp hit his head.

It seemed he opened his eyes mere seconds later. Snow filled his nostrils until he raised his head; once he did, the scent of smoke engulfed him. The crackle of the fires was nearly drowned by screams that would not end. He scrambled to his feet, the snow beneath him stained crimson as if with wine, and stumbled away from the slaughter and toward the trees.

And so now he ran, torn by despair and fear, amazed that his matchstick legs could outrun the sinewy limbs of the armored horses and the fiery wrath of their riders’ flamethrowers. He wished he could have found—could have lifted—the ax that had been his father’s, with its handle longer than his arm, and swung it into the chest of anyone who dared approach his mother. He wished he had not left her when she pushed him out of their home. He wished he had not seen her blood upon the floor. He wished someone would have come to their village to cure instead of to eradicate.

The forest echoed with the shrieks of women who fought and pled and bled as gloved soldiers dragged them through the streets and pushed them into burning homes, of men as their hands—along with the pitchforks or knives they held in them—were severed by swords whetted on the bones of prior villagers, of children who collapsed when those who chased them flung torches at their backs. And above all this, the haunting croon of a pipe, promising all that a hurt little boy could desire, and so to that piping this little boy fled.

The more he ran, the stronger he felt. When he could no longer hear the screams and the flames, the boy realized what the song said, even though there were no words. It spoke of melted snows and rays of sun that embraced all whom they touched like warm knit sweaters. It spoke of a father who opened his eyes as color filled his cheeks and laughter spilled from his mouth. It spoke of a mother whose skin was smooth and soft and smelled of vanilla and kneaded bread. It spoke of brothers and sisters who danced and teased and loved and lived, who picked him up when he scarred his knees and told him stories when he could not sleep. It spoke of a world where bad things couldn’t come, where he could be free to grow old and weathered and well-loved like the most kindly of grandfathers.

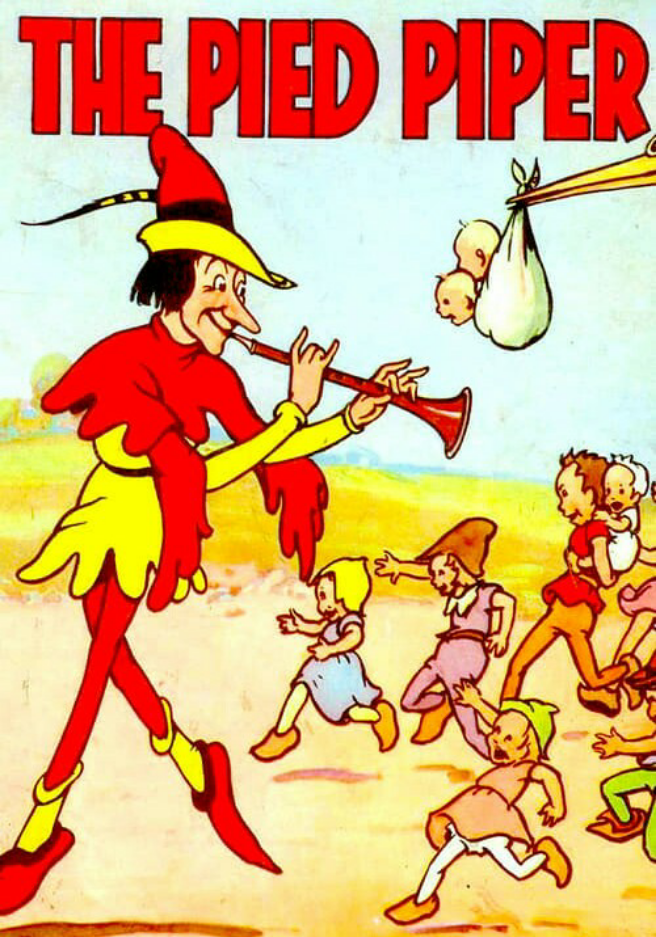

The boy ran faster, fast enough that it felt like he flew, anxious to get to the world the song spoke of. He even began to catch glimpses of the piper through the trees. Though he scampered and danced as he played his pipe, he appeared sometimes before, sometimes behind, and sometimes beside the boy. He wore a black hooded cloak that hid his face. Beneath it his clothes were pied, a patchwork of vibrant color impossible to miss whenever the wind whipped back the cloak. His pipe and fingers were white, of bone.

And just like the boy, he left no footprints in the snow.