As High As It Gets

As High As It Gets

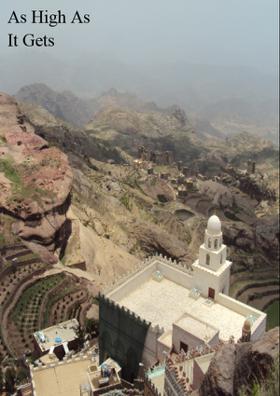

How would you define medieval? How would you like to step back into time and see how people of ancient times lived in houses made of stone or mud? How would it be to suddenly come across a tribal chief with a huge dagger stuck in his waistband? How does it feel to ride a mule atop a scraggy mountain slope, fearing a fall so deep into a valley that even your bones would get shattered into pieces? All this may not appeal to someone looking for an ideal getaway. But it suited me just fine because I was finally back home to the place where it had all started. I was in Shibam, the highest region in Yemen, located at a height of 9,000 feet above sea level. With about 7,000 inhabitants, Shibam is reported to date back to the third century AD and was the capital of the then flourishing Hadramaut Kingdom.

My journey to Shibam was the culmination of a long tour through the cities of Aden and Sanaa in Yemen in a bid to know more about the country where I was born. And like the proverbial icing on the cake, Shibam seemed to be the perfect destination to cap it all. The small city, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, owes its fame to its distinct architecture. The houses of Shibam are all made out of mud brick or stone and about 500 of them are tower houses which rise five to 11 stories high, with each floor having one or two rooms. “This architectural style was used in order to protect residents from Bedouin attacks. While Shibam has been in existence for an estimated 1,700 years, most of the city’s houses originate from the 16th century. Many, though, have been rebuilt numerous times in the last few centuries,” explains a guide.

Often referred to as the oldest skyscraper city in the world or the Manhattan of the desert, Shibam is a part of the sheer-sided Haraz Mountains that have, for centuries, acting as a cultural fortress protecting the Yemeni heartland from interfering foreigners. These rise from the steamy coastal plains of the Red Sea and through foreign invasion is now a thing of the past, what has not changed is the breathtaking grandeur of the mountains and the beauty of their tapestry defined by terraced fields and fortified villages, some of them perched so precariously on the slopes that it seems as if a rolling pebble is all that it would take to push them down. With weather that remains persistently cold throughout the year, the guide tells me that it’s good I have come during the summer. My unending sniffles and cough state otherwise. And the afternoon rains with ice flakes don’t really spell a summer as we know it.

Each town in the Haraz region is built like a castle with the houses themselves forming the wall, equipped with one or two easily defensible doors. Constructed from sandstone and basalt, the buildings are perfectly integrated into the landscape and it is difficult to tell where the rock and the village begins or ends. The mountain is divided into terraces of a few acres or more, separated by walls sometimes several meters high. On these remarkable terraced fields grow alfalfa for livestock, millet, lentils, large areas for coffee and qat. Incidentally, chewing qat leaves is one of the favourite indulgences of Yemenis and also one of the negative aspects of the country. Classified as a “drug of abuse that can produce mild to moderate psychological dependence” by the World Health Organisation, qat’s physical symptoms can include high blood pressure, tooth decay, constipation, hemorrhoids, hallucinations, and depression.

But my mind was more on absorbing the beauty of Shibam. The whole area offers views that you may have never seen before, all the more spectacular because of the seemingly unending horizon of mountain peaks and the ‘rawness’ of the landscape. For a tourist, the Haraz region also offers a peek into the ways of Yemeni lifestyle, shorn of all the modern trappings of urban existence. Here, living is basically a way to survive and each day is taken on its own merit with not much to look forward to in the future. On the cultural side, the dancing in Haraz is one of the more amazing sights and this can be witnessed only if you are invited to a wedding. An alternative is to watch it being performed at the Al Hajjerah Tourist Hotel in Manakhah. One of the areas worth visiting is Beni Ismail which is famous for its coffee and the special technique used to grow it.

Within a day’s journey are Banu Mora and other villages located on the ridge overlooking Manakhah, which is the heart of this prosperous mountain range – a large town whose market attracts villagers from the entire neighbourhood. Al Hajjara, to the west of Manakhah, is a beautiful walled village whose citadel was found in the 12th century by the Sulaihids. From there, other villages are accessible, including Bayt al-Qamus and Bayt Shimran. The village of Al Hutaib, which is my last stop before returning home, is built on a platform of red sandstone, facing a magnificent view of terraced hills which host a score of villages. Here also is the mausoleum of the third Yemeni ‘dai’ Syedna Hatim al-Hamdi. Bohras from the world over gather here to offer their respects and the local Ismailis have tarred the roads and paved the streets for their believers, without damaging the landscape.

Over a cup of coffee in the morning before I board the bus, a Yemeni chats with me in some basic Arabic that I can manage to understand. “I have travelled to many countries and have witnessed fascinating sights, most of them built to attract tourists. But at the end of every such visit, my heart has always yearned to quickly return to these mountains. We are short of resources – there’s very little water, the terrain is rugged, there’s power shortage, the weather can be intimidating and tribal warfare keeps us on the edge. And yet, when I sit here in front of these mountains, I feel so close to God – and to myself,” he says.