Thalaikoothal

Thalaikoothal

2016

Muniyamma was wailing and bawling while narrating her story. It was difficult for me to guess her age. She was over exposed to the Sun and the weather and she looked like a withered plant. Fragile in body but full of spirits. Years of collecting medicinal plants from the surroundings of the pond, harvested fields and roadside and scrub jungle a little distant away from her hamlet, involving hard work, back breaking and humiliating had left her withered. She might be in fifties but looked to be on the wrong side of sixty. Her body bent like a question mark as if asking what is the point of her life?

She stopped wailing a bit and told us about her grandmother. She talked of a ceremony called “thalaikoothal” in which her grandmother was assisted to die prevalent in those parts of Tamilnadu, a southern state from which she hails. She said her grandma’s family was so poor they could not afford to feed her even a single meal. As per customs not sanctioned by law, the son in consultation with elderly in the family and the priest fixes an auspicious day. Grandma was given a ceremonial oil bath which cools the body considerably and is fed with coconut water which aids the colling further and is left to die. If one is lucky the death happens soon enough. “Grandma was lucky,” Muniyamma said as she died that night itself. It was a hush-hush custom. Muniyamma said she could have gone her grandma’s way but for the kuzhu (self-help women’s group) of which she herself was a member.

The tea and biscuits came and she took a break from the narration. I asked her to elaborate further. Muniyamma continued her narration. From as long she can remember she went with her mother to collect medicinal plants and shrubs. They will set out in the wee hours in the morning with some other women and by mid-day manage to collect a bagful of medicinal plants. They would come and dry them in front and back of the house. Once it was sufficiently dried, they would bag it and head load it to the nearest bus stop, take a bus to the district head-quarters where there are some traders who would give them some pittance according to their whim. What happens to their collection, she didn’t know. That is how they eked out a living humiliated in the process by the bus conductors, co-passenger and by the trader and his men. When I asked her about her parents, she said her mother succumbed to a snake while collecting herbs in the field and her father had died as an alcoholic due to severe liver disease.

A few years back she said some women came and formed this self-help group. She was told that they would buy their medicinal plants at the village herself. She thought the idea was good as it saved all the harassment. The group lived up to the promise. They would collect once a week; weighment is done in front of them. They even gave some tips about how to clean the dried medicinal plants and gave it a better price. She earns some money each week for most of the year. She hands over the money to her daughter-in-law. That’s how she manages to get some gruel and vegetable twice a day or at-least once a day. That is how she keeps herself going. There are a few women too that the kuzhu provides succour. She also added as far she knows some NGO started this kuzhu and the medicinal plants collection effort and a company sends them in bulk to some neighbouring state.

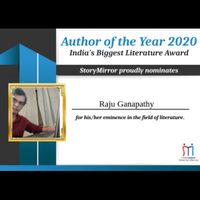

Hearing Muniyamma’s story gladdened my heart as I was the founder of the company she referred to. One needs to under the context in which the idea of such a company had come up.

When the British ruled India they saw the forests for its worth in terms of timber for ship building and expansion of railways. Various laws were passed giving ownership of the forest to the state and alienating the community which were dependent on it. While forest symbolised timber for the empire for the community it meant food, fodder, fuel-wood and medicinal plants. The forest laws continued to reflect the state monopoly even in independent India. It was very telling when a professor from a reputed management institute once made a presentation by imposing map of thickly forested state and prevalence of high level of poverty, they were coincident. High forest meant alienation of community and high incidence of poverty. These states also saw the emergence of Naxalite movements that threatened to derail the state’s power.

In 1985 when Rajiv Gandhi took over the prime ministership with an unprecedented mandate, he established the National Wastelands Development Board and called for a people’s movement to restore ecological balance. Against the suggested requirement of one-third under forest India had only 18-19% of land under forest cover. But the movement never took off and communities continued to remain alienated and poor. Importance of bio-diversity conversation was rising throughout the world and grants were made available to researchers to study its importance and relation to human life. I won a competitive grant and undertook a study of community initiatives in forest protection and restoration. The research took me to Bengal, Orissa and parts of Gujarat. The communities had developed a set of rules to protect and use of forests outside the mandate of the Indian forest legislations.

The theory of common property resources was emerging on the horizon. From the despairing ‘tragedy of commons’ there was hope rested on community management of resources. Ostrom’s nine principle stated that communities can manage common resources successfully. She went on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics for her theory in 2008.

Genesis

At the foot hills of Aravalli mountains, in a non-descript tribal village called Nanisara a few men had gathered to discuss about the state of forest and their inter-twined life. Siddharth bhai as he was respectfully called had arranged for this gathering at the request of a representative non-government organisation who was also present. It was outside his modest hut on the courtyard. He himself had swept the courtyard to free itself from dust. He was a Gandhian and believed in self-help. He was one among the tribal (Bhil) men gathered there but was now a city resident as he teaching at a Gandhian institution having done his doctorate in sociology, a miracle considering it was only a rare Adivasi (tribal) that underwent education.

Siddharth was in his late fifties. He himself had seen better forest in his younger days and his grand-father had regaled him with stories of wild animals and Bhil way of living in tune with the forest. He was remembering the memories in the morning gathering of tribal men. Forest stands denuded now and Bhils have taken to agriculture but forest regeneration was essential to sustain the agriculture and environment. The ritual annual forest hunt and sharing of the bounty became a thing of the past.

We must do something Siddharth urged the leaders around. The NGO representative added that the government wants people to restore forests and they are willing to give rights that has been taken away from the people.

Siddharth bhai added that under the colonial rule forest became a state monopoly and people especially tribals like us were divested of our rights. The colonial ruler managed the forest for timber that helped build railways and shipping industry. Where-as tribals were using a variety of forest produce like fruits, fodder, small timber for ploughs and house construction. Our chacha (uncle), as the grand old tribal living in the adjoining village Bhapur, was a medicine man of great fame. He knew how to treat people for a variety of ailments including common fever, cold and even he could fix broken bones Siddharth bhai said.

The men who had gathered there were leaders in their own rights and respected by the villages they inhabited. They nodded in agreement until one of them asked. What do we do about? What is the meaning of this gathering?

The NGO representative now took over and said we are here to discuss a government order of letting people protect forests with rights to collect fuelwood, fodder, medicinal plants. Government would also support establishing a small nursery and trees could be raised and planted in the forest. But the community must resolve to protect the forest and form a cooperative. We as a Ngo would help in dealing with the process of registering a cooperative and be your spokesman vis-à-vis the government. But you as a community must from forest patrol and take care of forest against pilferage etc.

Some murmurs were heard and some discussion took place. The leaders agreed that this must be done but they have to hold meetings in their villages. One of the leaders suggested that women folks must also be involved as they go for fuelwood collection and youth take the animals to the forest was grazing. Another leader suggested that idea of nursery was good and we must in consultation with chacha must replant some medicinal plants too. How about repair of the ponds adjoining the forest? Asked another leader. If we can get to repair such ponds in some of our villages, drought prevention can be done.

The meeting dispersed with tentative agreement that they shall gather in another fortnight but by then village level meetings would have been undertaken and an opinion of communities at large taken. The NGO representative also committed to attend these village level meetings.

Two weeks later at the appointed place in Nanisara more people had gathered. There were some women too. The NGO representative had learnt about an ongoing practise of forest protection and fodder harvesting in one of the distant villages and requested its leader to be there. The leader Magan bhai, talked of how they are managing fodder by not letting cattle during post monsoon and letting the seeds fall. They had devised a system to harvest once the monsoon got over and new shoots of grasses had started sprouting. The harvest continued in section of the forest where in one representative from every family could bring a sickle and harvest a head load of forest each day. This continued until there was nothing to harvest and the forest opened for grazing until the next monsoon. They had employed some youth as forest guards who were paid in kind of additional fodder for their milch animals. The gathering had appreciated this indigenous system and said one must devise such methods for our forest protection too.

The meeting ended with a positive note that the leaders would now enrol membership in the tree growers’ cooperative which with the NGO help they would formally register and enter into an arrangement with the forest department for some way of formal agreements. The meeting also suggested that they form a night patrol to guard the forest in groups of four where in representatives from every family would volunteer to give time and effort.

Bhils march to their own beat. Their beat is in resonance with that of the earth and forest. Their dance consists of this beat and if one were to hear it one would tap one’s feet unconsciously to the beat. The drums were out and in some of the villages, youth took out the drums and started the beat as they went around the village and talked of the new movement. Many joined and marched to the beat.

Kranti bhai was a dominant leader from the Manpur village and promised that they would start a green revolution by way of forest regeneration. Kallu bhai from Bhapur village sang a song extoling the virtues of Bhil-forest relationship of the past.

NGO representative went with Kallu bhai to meet chacha and talk with him. Chacha was an old and didn’t know how old he was. Kallu bhai said he must be at least in his nineties. He had become fragile but managed to do his daily chores without troubling his family members. Chacha recalled that he was the medicine man and he had travelled to all the villages in the tehsil (block). He would get invited by some-one or other for treatment. It could be for fever, snake bites, broken bones, stomach infection or skin ailments, women’s ailments related to period and so on. He had a combination of herbs that were available in the forest for treatment. He said he also used some animal products like talons, beaks and bones for treatment. he was taught by another medicine man with whom he had apprenticed. They didn’t keep any note book as they were un-read. It was all from practice and memory. If forest can be regenerated medicinal plants would come up too. Then he can pass of some of his knowledge a lot of which he has forgotten. I was taken aback when chacha casually mentioned that he could treat stomach condition that I was suffering from. How the hell he knew that I had irritational bowel syndrome I loudly wondered? Kallu said chacha was like that. He can see physical signs of health conditions within bodies what normal people cannot see. He can feel the pulse and talk a lot about one’s health condition.

In the ensuing period an exciting movement got started. Within two years when protection chacha was conducting tutorials with youth in his village and neighbouring villages how to treat simple ailment with herbs. These had started sprouting again. A few months later Urmila was the only one to continue practising tribal medicine. When the NGO representative bumped into her, she told him her first case was a scorpion sting in her village and she managed to cure the boy. She mentioned she had made a paste of chirchiri and ghatayan both local herbs that became available with forest protection and applied it on the sting.

As Magan bhai had stated grasses became available in plenty with the introduced system of protection. The movement attracted some government officers who attended the monthly meeting at the premise of the NGO and shared information about some government schemes for growing fruit orchards, construction of bio-gas plants which were unknown to the community. The community leaders welcomed these schemes and facilitated implementation in their villages. It was a win-win situation.

1997-98

Seed Germinates

I went back to my alma mater with this dream of a seed sown in the oasis of my mind. The alma mater was founded by the biggest development story of dairy cooperatives establishing their own brand of milk and allied products. It was called AMUL, the” Taste of India.” I bagged a grant and soon set out in search of this dream. I visited the forest areas, talked to tribal communities who gathered these medicinal plants, went to the Forest Department to get data; met with traders to understand the supply chain; had meetings with manufacturers who made traditional medicines out of these medicinal plants in Mumbai and Amritsar; by a chance meeting attended the workshop in Bangalore on medicinal plants organised by a pioneering non-governmental organization; who got interested in my idea and provided a platform for me to explore further. Having been a product of the AMUL (top dairy brand in India today, owned by farmers’ cooperatives) school of cooperatives I started dreaming if something likewise can be attempted in the area of medicinal plants collection, value addition and ownership.

1998

Kranti bhai went up to Delhi. He was being presented Indira Priyadarshini Award for Environment restoration in his village by the ministry of environment, Government of India. Kranti bhai in his inimitable style stated that the award was a recognition to the collective effort in the Tehsil by the Bhil communities at forest restoration. In about thirteen years-time, ten thousand hectares, nearly one-third of forest was under restoration through community protection. Their ekta (collective) had restored the vagado (forest). This award fur cemented the conviction that such an idea could actually become possible.

In my own work with an NGO referred to above in Gujarat nearly one-third of forests was under brought under restoration through community protection in a tribal dominated area. One thing became clear in all these efforts that communities were interested in what is called as on-timber forest produce (NTFPs in short), medicinal plants constituted an important segment of this. By now I had spent over a decade in the area of community forest management. I became restless that I need to do something more.

Village Herbs

At the Bangalore conference on medicinal plants, I had met the NGO who was willing to provide me a platform to explore my dream. The NGO was already running a program on medicinal plants with a network of ten other NGOs in the southern states of India.

It is said that when all the cells in one’s body desire badly something then the universe conspires to fulfil that desire. I saw my desire taking shape when the universe conspired to help me in my journey. It came in the form of a chartered accountant who understood this dream. It was followed by a help from a marketing maverick who decided to quit his corporate career when he was trekking in the Himalayas in Shiva’s abode.

Village Herbs a public limited company with shares being held by self-help groups of medicinal plants gatherer women got registered. Further help came in the form of a nattu vaidyan (indigenous medicine practitioner) who shared formulations from his family records. Formulations consisted of local herbs that were easily available. Then help came in the form of Jyoti (literally means light) who showed us the path for getting license for manufacturing these indigenous medicines. Many other self-help groups of women joined hands in selling these medicines in the villages they worked themselves. First slew of medicines providing first-aid care for medical conditions commonly prevalent were produced by Village Herbs. The idea was to have about 20 such medicines in the kitty. A dream of locally available herbs, manufactured locally and sold locally by the self-help groups of women. Go vocal for local as the present-day Indian PM was fond of saying. At the height Village Herbs sold medicines in about eight Indian states through self-help groups.

2007

If dreams could sour and turn into nightmares, then that is what happened in my case. After some initial excitement of having entered the market place the efforts could not be sustained. I had already exhausted my inner resource. Each day for me became a challenge. It was those days when unlike today’s start-ups Village Herbs didn’t have easy access to resources or technology. The world had not heard of the term social enterprise. My sympathetic chairman had one day observed that my smiles have all vanished from my face and left with a permanent frown. His observation was the last straw on my back. I told the company board that I could not manage Village Herbs as I didn’t have it in me.

2016

Imagine my delight when I had met Muniyamma years later and heard of her thalaikoothal story. It made my life better to know that though my dream ended like a glass half-filled it didn’t remain empty after all.